Our Primary has a mixture of pupils from different backgrounds, but who are predominantly white European. We have some Polish children, and some Spanish and Italian, but the vast majority are British and from a range of different socio-economic backgrounds. We have about 7% of pupils having free school meals (the national average is currently 18% according to Department of Education figures).

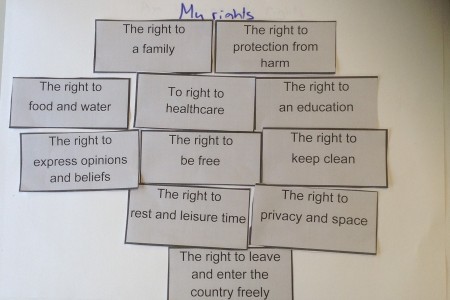

I was interested in finding out more about pupils’ attitudes and values and decided to ask them questions about Human Rights, to find out whether there were areas of this work that needed attention. I chose a group of Year 5/6 pupils (age 9 to 11) and divided them into pairs. Each pair had a collection of the Human Rights cards, and I asked them to consider which human rights were the most important to them. Their most popular choices were the right to food and water, to healthcare, to protection from harm and to an education. Very few chose the right to leave and enter the country. Their discussion about the right to a family led to some insights into the criteria they were using for choosing their cards. Most pupils thought that because some people don’t have a family, they are able to choose not to have a family, then it isn’t a human right. This suggests that pupils were confusing the fact of having the right with the regularity of accessing it. It seemed that they thought rights were something you had to have. If you are able to choose not to have it, then it is not a right.

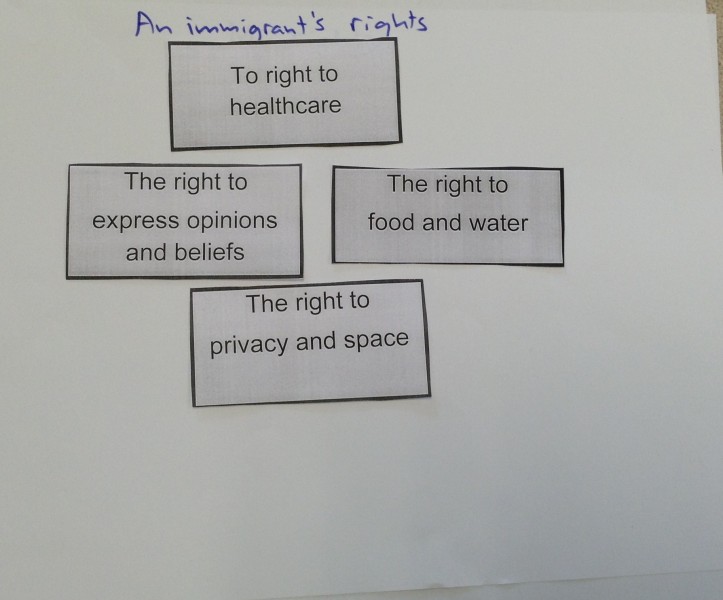

Then we thought about it again, substituting the word ‘me’ for the word ‘immigrant’. The pupils were in agreement that an immigrant also has the right to food and water and healthcare, but they were unsure about the other rights. A prevailing view was that if you choose to leave your country and go to another country, you forfeit your rights. They believed that most immigrants come here illegally, and in containers, and so they should not have the same rights as indigenous people. They identified a difference between children and adults, in that children who emigrate may not have chosen to leave their country. They were quite adamant that as we live here in the UK, we have more rights than someone who has moved here for work.

After some discussion, pupils began to think about people who might have left their country without much choice. They talked about people born in African countries, and they fell back on stereotypes of poverty, believing that there is no food, it’s too hot and the healthcare is inadequate, so people are forced to leave their countries, and they are less at fault in that circumstance. They also felt that in Africa, the laws that would protect human rights aren’t as good as they are in this country.

Then the conversation moved to talking about the rights of a British person who is in poverty or is homeless. The pupils believed that poverty in this country is due to someone being naughty, or not behaving properly, and that justifies those people’s lack of rights.

The conversation quickly moved to prevailing stereotypes about immigrants in the UK; the pupils were clearly repeating tabloid headlines and attitudes from parents at home. They expressed the view that an immigrant in the UK can work very little but earn lots of money, take food from food-banks and get free housing.

I was concerned about the lack of critical awareness in the pupils at this point and was keen to keep the conversation going, in order to encourage them to question and problematise the issues as much as possible. I asked the pupils whether they applied the same feelings to me, an immigrant to the UK. They were shocked to be reminded that I was from a different country, but they decided it was a different situation: because I speak English and have a job and a family, those factors automatically gave me more rights. They didn’t see me as fitting in to the narrative of the illegal immigrant.

To move their views on, we explored different types of immigration. We talked about the Polish children in their school and all the different reasons that they had moved here. We explored different reasons for migrating: for work, for family, or to try somewhere new.

We also talked about refugees. The pupils were doing a significant project on refugees at school at the time, but they were failing to make connections between the media headline attitudes they held about immigrants, and people who leave home due to conflict and danger.

At the end of this conversation, I sent the pupils off to the playground and asked them to think carefully about the conversation. During break time, two pupils came back and said that they had changed their minds, they felt that we are all people and we all have rights. They were children who were previously vocalising the opposite of that view, so the conversation alone, the opportunity to discuss the issue, had really changed their perception.

Long term, our plan is to address some of these attitudes through our work on Fair Trade and living standards, trying to help them understand the causes of poverty, that it is more than just laziness or bad behaviour. We want to challenge the idea that immigration is illegal and all immigrants come from poor countries, by focussing our work on issues of social justice, looking at the many different reasons for the choices people make in their lives, and exploring diversity in the UK more.

When I considered whether the extensive work we do on refugees was having the impact we wanted it to, I identified that the children were failing to make links between aspects of their learning and the world around them. So, when we plan our WW1 topic, we will make links to current issues and contemporary conflict. When we talk about refugees we will broaden the topic out to include other global and local issues, to encourage children to make connections.

The thing that really stood out was hearing the children repeat things they had heard on the news, or heard their parents say, without any criticality or questioning, and with complete certainty to start with. The impact that one classroom discussion had, where I problematised the issue for them, was surprising. We are going to use Philosophy for Children techniques to continue to explore these issues, and to enable the children to think critically about the media and the views they hear expressed by others.

We’re a Catholic school and it’s a basic Christian value to welcome people and integrate people, to respect others. This is something we want to run through all the work we do here.