Background

Ours is a large Primary school in North London, with approximately 645 students, who are representative of the demographic of the local area. The majority of pupils at the school are from black and minority ethnic backgrounds, with a high proportion of children learning English as an additional language. Approximately 58% of pupils are eligible for free school meals. These are available to pupils from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (the national average for Primary school pupils is 18%).

We have recently finished a two-year School Improvement Plan (SIP) in which Learning to Live Together was a strand. This strand focussed on three key objectives:

- Re-design of the Federation Curriculum

- Achieving the Rights Respecting Schools Award (RRSA)

- Developing and maintaining global linking partnerships.

The school ethos has transformed through the work on the SIP to have global learning and a social justice mentality as its ethos. The 2014 curriculum has been developed and is currently being launched based around themes of social justice and a focus on shared humanity, challenging stereotypes, identity and globalisation.

Initial audit/measuring activity

We were part of a working group at the Humanities Education Centre in Tower Hamlets. With this group we designed attitudinal assessment activities based around core literacy texts. This was especially useful for my school context due to the fact that our curriculum is also designed around core texts.

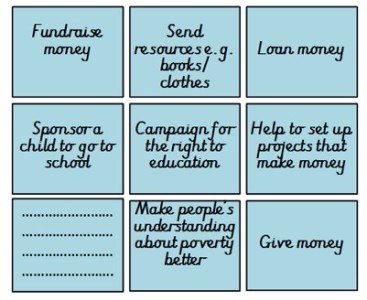

The activity trialled in this instance was based on the book One Hen and was assessing attitudes towards How can we support and help people living in poverty? One Hen is a text about microfinance and its impact on a community. The activity consisted of a diamond ranking activity of nine methods of supporting people living in poverty. These were loaded with opposite methods to measure whether children selected charitable methods or those with a stronger social justice theme.

I trialled this activity with my Year 6 class (age 10 to 11). From my knowledge of the children, I assumed that the majority of children would prioritise giving and fundraising money over lending money.

The children were provided with the following options to prioritise:

These were cut up to avoid implying priorities to the pupils. A blank card was also included to assess children’s own concepts of how they might make a difference to poverty.

On the whole, my teacher assumptions were correct and the majority of children placed give money/ fundraise money towards the top of their priority listing. Loan money was regularly towards the bottom of the ranking, with many groups putting it as having the least impact on making a difference to poverty.

When questioned as to why they had ranked their actions in this way, pupils gave a variety of responses. One group stated that when lending money You want it back and it won’t help. Similarly, another child suggested that loaning money was like not giving money at all. Other children had concerns about whether or not people would be able to repay the loan stating: they might not be able to pay it back.

There was also a large focus amongst the children on education. One group in particular used their blank card to add in free education everywhere. When questioned regarding this the child responded: some countries can’t afford to make education free. It is my opinion that this could be a product of the school using the UNICEF Rights Respecting Schools Award to underpin the behaviour policy. The term right to education is used frequently throughout the school charter for behaviour and children are engaged in this understanding of rights.

From the findings, I designed a range of activities based on microfinance and sustainability. The objective of these activities was to make children more critical of the sustainability of actions towards poverty and provide them with a clear understanding that microfinance was a potential model for making a difference to poverty.

Global Learning – the activities in-between

After listening to One Hen, the children engaged in reading comprehension activities based on the story throughout the following week. Accessing the One Hen website, children engaged in quizzes about the book and story-mapping exercises as guided reading activities. The book was also acted out as part of a whole-class guided reading,* with the video of the real Kojo being played.

In addition a discrete lesson about microfinance was taught through the humanities. Initially children were given examples of case studies of people who had received microfinance. Children were expected to read the text and answer two questions in line with the school’s RRSA teaching objectives:

- Before the microfinance loan, what rights did this person not have respected?

- How did the loan support the person to have their rights respected?

The lesson then moved on to an activity involving writing a letter to Kojo from One Hen. Children were provided with a scaffold ** for sentence starters for the key themes expected in the letter. The main aims were to get children to explain what microfinance was and how microfinance could impact on people’s rights.

This activity was a success and showed that the children had understood the underlying premises of microfinance and the methods by which it works.

Final audit

The How do we make a difference to poverty? activity was repeated after this sequence of activities in exactly the same format as the baseline activity. This was not modified from the initial audit in order to assess changes exactly.

On the whole, pupils moved Loan money towards the top of their priorities. Fundraise money and Give money did not move to the bottom of the priorities in all cases but in many cases lending money had taken precedence over fundraising. This shows a clear move towards a social justice mentality and away from the charitable view.

Reflection on whole process

The process was an interesting beginning to the scheme of work and gave clear support for teaching points. The scheme of work in-between needs careful design so that it is not misleading. There is a danger that the teacher can become too focussed on the opposite to fundraising, when this also has a place.

The most telling assessment opportunities were the conversation generated throughout this activity – the qualitative aspect. As a teacher working solo in a classroom, this was hard to capture. My suggestion would be to record conversation to delve deeper into the comments at a later point.

*In whole-class guided reading there is one objective, and one text. But various activities (e.g. word-searches, dictionary skills, reading in pairs, quizzes) are devised according to different pupil abilities, so that everyone can participate and be challenged.

** ‘Scaffolding’ is support given during the learning process to help learners to progress. Linguistic scaffolding, for example, involves using language one step ahead of the learner’s, but which is easily understood by him/her. Vygotsky refered to this as the ‘zone of proximal development.’