What do I want to find out?

Whether pupils hold preconceived ideas about different people and places.

What do I need?

- A set of statements about a boy living in an unnamed country,

- An outline map of the world shared between 3 or 4 pupils

- An A4 sheet of paper and coloured pens for each pupil

What do I do?

Timing: 15 minutes plus discussion time

- Where all your pupils can clearly see, write the following statements about a boy called David/Daud who lives in an unnamed country.

He has four siblings.

They keep chickens at home.

His mother is a hairdresser.

His father works in a factory but is worried it might close down.

While his parents are at work, David/Daud’s grandparents take care of his younger siblings.

One day he would like to live in another country.

Faith is important for the whole family.

The school is 10 km from his home.

When he gets home from school, he has to help his family.

The nearest hospital is 30 km away.

Sometimes, there is no electricity.

The mobile phone signal is unreliable.

- Give each pupil a sheet of A4 paper and coloured pens.

- Ask the pupils to make a simple annotated drawing of where David/Daud lives, and what they think the future holds for him.

- When they have finished drawing, they should discuss their pictures in groups of three and explain to one another what they have drawn.

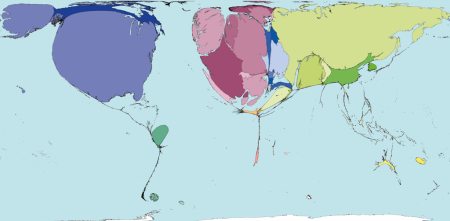

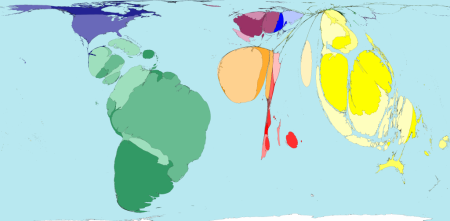

- At the same time they should mark on a blank map the country, region or continent where they think David/Daud lives.

- Each group should present to the class the place where they think David/Daud lives, and what they think about his future, provide reasons and mark the location on the blank map.

- Ask them to note down which statements were key for their decisions about the country David/Daud lives in.

- Record their answers and any comments made

How do I analyse the results?

- Note down responses in the recording template that is available on the website, recording whether they place David/Daud in the Minority World or Majority World and record justifications.

- Observe whether the pupils imagine a life of poverty or wealth for David/Daud. Do they assign him a life full of opportunities or, on the contrary, do they assume that his options are rather limited? What is his religion according to the pupils?

- Record which statements were key for their decisions about the country David/Daud lives in and look for any patterns.

How do I measure the change?

- Depending on the time between each audit, you can repeat the activity exactly, or you may want to conduct the initial audit with a sample group from the class, and use a different group of pupils for the follow up audit.

- You can use Majority World or Minority World? or What would you see in Africa? As alternatives.

- Look for a shift in pupils´ understanding that David/Daud could live anywhere in the world and whether pupils realise that both the inhabitants of the Minority and Majority World could face each situation.

- Note comments that are critical of the activity itself or relate to stereotypes.

- Record whether pupils are less certain, better able to debate and discuss and more or less willing to take part in the activity.

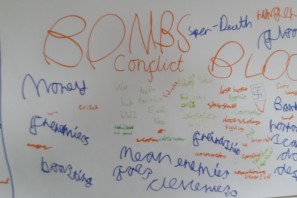

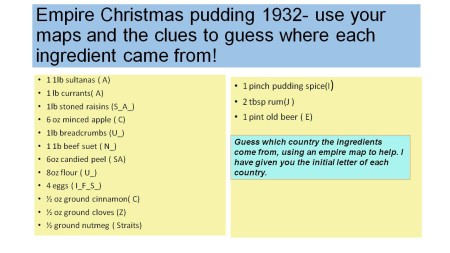

Ask pupils working individually to divide their paper in half and write down everything they associate with ‘peace’ on one side and ‘conflict’ on the other. Collect this work and keep it safe.

Ask pupils working individually to divide their paper in half and write down everything they associate with ‘peace’ on one side and ‘conflict’ on the other. Collect this work and keep it safe.