Background

Ours is an all-through (Primary and Secondary, age 3 – 18) school, with 2,400 students on the roll. We have links with four partner schools overseas, but also engage in wider global activities. Global learning is integrated well through several curriculum areas. The School Development Plan includes global learning, which is fostered throughout the school.

What did we want to find out?

Together with our partner school in India we wanted to establish the students’ level of awareness about the reasons for poverty and compare findings. As part of this process, we wanted to find out what action students would be prompted to take in order to make a difference. It was assumed by teachers from both schools that students would have some knowledge about the reasons behind hunger.

We wanted:

- To establish a sense of empathy among pupils, and encourage them to reflect.

- To motivate students to develop debating and critical thinking skills, which would enable them, as well as their community, to take action to make a positive contribution to reducing poverty.

- To develop a sense of personal responsibility and to appreciate how this could have positive impacts both locally and globally.

Initial audit/measuring activity

The activity Why are people hungry? was used in our school, and in our partner school in India. It was used to introduce a generic global activity. This activity generated good group discussion and debate.

We modified the method by using hexagon shapes as well as a diamond to collect and analyse the data.

Key comments included:

I got the most important information from this activity which was that food was not shared out fairly. So this year in the elections I’ll tell my parents to choose the right one for the seat of prime minister who can improve our country

Year 7 student, Partner School (India)

We learnt that farmers do not use new ways of growing food

Year 7 student, Partner School (India)

We learned that people are not only hungry because they may be poor, but also other reasons like war. If nothing is done to stop wars there will be more hungry people

Year 7, UK School

Before doing this activity, I thought the only reasons for hunger were because there wasn’t enough food for all the people in the world, nor enough electricity etc to grow the food. I didn’t realise poor farmers couldn’t or weren’t allowed to sell to rich countries like Britain.

Year 13 student, UK School

Key objectives set were:

- to enable a successful bridge between partner schools that could be repeated in future years;

- to develop higher-order critical thinking and evaluation skills.

Global Learning Activities in between

After the initial assessment, students were keen to find the right answer. Teachers helped expand the debate, providing video links, PowerPoint presentations and work sheets. This occupied one week of Personal Social and Health Education and over two weeks of Economics and Business Studies.

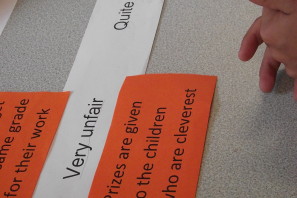

BTEC Business Studies students were sorted into small groups to work on a high-to-low ranking list before doing a diamond ranking. They were then asked to propose a potential topic heading (rather than being given one). Most proposed poverty, third world and hunger. They then rearranged the cards into a diamond 9, where they could debate competing items at level 2. A clip on world hunger was then shown, with students still kept guessing as to how this related to business studies. The International Business unit incorporates an element on business ethics, which is what the students had to research next. After two weeks, they were asked to revisit the diamond ranking activity and assess whether their opinions had changed.

Both of our objectives have been met, as the partner schools have engaged in the hunger activity over two years. Having honed these skills, BTEC and A level students (age 16+) were able to link the causes of hunger to other matters in the supply chain, and critically evaluate the consequences of these in essays.

Final audit

Our final audit focused on Business Studies and Economics students. We used the given recording template, (available on the website) to record our findings:

- All students were now familiar with four out of the nine reasons illustrated for why people are hungry, namely:

- There is not enough food to go round

- Food is not shared out fairly

- People are too poor to buy food

- There are too many people

- An extra 10% students were additionally aware why farmers don’t use new ways of growing more food. However, most of these were Geography students.

- No students were familiar with the following reasons:

- People in rich countries don’t give enough money to charities

- People can’t grow because of wars

- Poor farmers are not allowed to sell their food to rich countries

- The best land is used to grow food for other countries

What did we discover?

The activity needed taught data and information, which then influenced students to produce different results. As is evident from some of the student quotes above, some of the factors highlighted showed that the students had to be taught how farmers are limited as to which countries they could sell to. Once students were aware of this, they became better-informed decision-makers which, the second time round, resulted in more considered debate and decisions. Overall, the students were really engaged and asked a lot of questions.

By the end of this process, all students could discuss the nine reasons, and whilst their opinions continued to differ, there was greater awareness of the reasons why people are hungry. Repeating the diamond ranking activity revealed changes in attitudes and intended actions. In both schools, over 50% of participating students changed their ranking of key reasons for hunger.

Way forward

As a result of this activity, it was decided that both partner schools would integrate teaching about the causes and consequences of poverty as a whole-school theme. This is currently being embedded into curriculum areas, assemblies and other areas of school/community life. This is straight forward as it complements the International Business unit of the BTEC National Business Award and was extended to the A Level Unit 4 award on Global Poverty, where the higher order evaluation and critical thinking skills were also used.

The activity was also useful for developing communication and debating skills amongst pupils with low participation in class activities.

What’s the most important thing we learned?

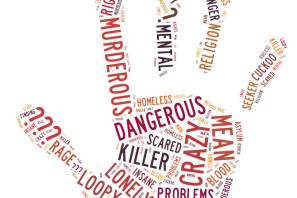

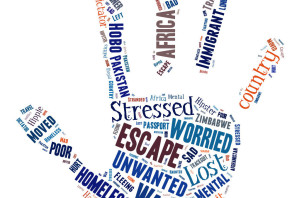

A significant proportion of our students came from homes where, as young children they qualified for free school meals, which means that their homes would be classified in a very low-income bracket. Their parents were mainly migrants, and may have experienced some level of poverty. The activity reminded them of the existence of both local and global poverty, and created a can-do-something approach towards making a difference, as they took the message back home to parents.

Were there any surprises?

Despite the majority of students witnessing poverty in Delhi, or coming from countries associated with poverty, new prosperity in those countries pushed concern about poverty into the background, where it has become invisible. This activity reminded students about a continued growing world divide between rich and poor.

What would we do differently next time?

Next time we would repeat the activity at the end as a final assessment, but keep the students in the same groups.

We may extend evaluation forms to include parents, so students can extend their learning and debate some of the issues at home. To further enhance the activity, the two partner schools have agreed to hold a video conference between students from each others’ schools, which will enable both sets of students to learn about local poverty and hunger in the UK and India.