This is a Professional school in the Czech Republic focused on Construction and Geodetics, located in an area with well-developed industry, agriculture and infrastructure. I have taught here for 13 years. I chose a structural engineering class of 27 students, mostly boys.

The choice of To build or not to build? was straightforward. I liked the universal nature of the topic and the variety of possible discussion topics. I hoped to ascertain how students would make decisions about a planned project to build a supermarket in a nearby town, where there are already two similar supermarkets.

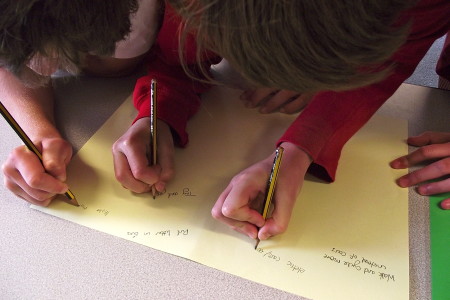

Working in groups, pupils had first to exchange views, and then reach a consensus and present this to their classmates. I recruited some younger pupils to film and photograph the activity, giving students the option to opt out if this bothered them. All students agreed to participate.

Initial audit

The 20 students present noted down ideas about the construction of the supermarket individually. 45% opposed the construction, objecting that popular, well-established shops existed already and that the proposed site would be better used for other purposes (agriculture or green space). Other reasons given were the possible job losses as existing stores might have to close; possible environmental pollution; the quality of available goods might drop; noise pollution would increase; and there would be more traffic.

Eight students welcomed the construction, citing potential improvement in the quality and choice of goods; greater proximity to customers; new job opportunities; and price decreases. Their approval was contingent on the supermarket being located on the outskirts of the town and stocking different goods from the existing shops. Three students were indifferent: the proposal concerned a neighbouring town and should be decided upon by those living there.

The students then worked in groups, discussing their views and coming to a consensus. One spokesperson from each group presented their opinions to the class.

Students reacted appropriately to the opinions of others, making perceptive arguments in such a way that more and more possible pros and cons emerged. New angles surfaced, including employment in the area, the possibility of competition among stores, and price wars.

At the end I added another element to the activity. I asked the spokespeople from each group to work together to encourage dialogue in the aim of finding a class consensus. The class decided not to approve the construction, reiterating the arguments voiced during the activity.

The results show that the students stressed the variety of goods and prices, but were also aware of possible problems affecting local employment, and local businesses, and the depletion of farmland. They considered it important to maintain local businesses and foster a competitive environment resulting from the appearance of a new player on the market. This would come at a cost of unnecessary waste of land and only make sense if the local population was involved in the process.

The students thought carefully about the topic, using their specialist subject knowledge, and understood problems inherent in building on farmland; employment issues in the construction sector; and the role of state and public administration. Based on the results I decided to focus on the topic of alternatives to supermarkets, specifically small shops and farmers’ markets. I shall also introduce students to the negative effects of the construction of supermarkets on the lives of people in the area around it.

Final audit

Only 15 students took part in the final audit, as some were helping out at a Primary school.

The goal of the final audit was to see if the students had changed their opinions. From individual students almost half favoured building the supermarket, four opposed it and four were indifferent!

Those in favour considered solely the residents of the town: jobs, flexible opening times, discounts and special sales. The students did not think about the effect of getting rid of the competition.

The reason some remained ambivalent was the lack of information, as a result of which they did not feel competent to make a decision. They would wish to know what products the supermarket would offer, how many new jobs it would create and who would finance the project.

In the reasoning against the supermarket the students cited a wider range of negative aspects connected with its construction:

- Traffic, pollution

- Building on land that can be used for other purposes (e.g. as farmland)

- Destruction of competition (and the unemployment connected with that)

- Aversion to supporting a foreign investor (and foreign produce)

These reasons go beyond the local significance of the problem and acquire a global character such as the transport of produce across long distances.

The discussion among students was more emotionally charged than during the initial audit. The results of the activity surprised me. I expected greater disapproval of the supermarket. Essentially the students did not change their views substantially from the first audit to the final one. However, they were far less certain about their decisions, and this necessitated including an undecided column in the second audit table that was not necessary in the initial audit. They were much more critically engaged, and this is reflected in the comments in the new undecided category.

Table of outputs from the trialling:

| Final audit | ||

| Individuals | Reasons | |

| agree | 8 | Better choice of goods, decrease or improvement in price and growth in the number of jobs, using up the plot, increased competition, smaller distance to stores, possible extension of opening hours, better quality goods, I’m not a competitive entrepreneur, discounts, location across town, the money for the plot will go to the municipality |

| disagree | 6 | I’m not a resident of this village, unnecessary, building on farmland, destroying local businesses, increase in traffic, price hikes, decrease in quality of goods, pollution of the environment, space could be better used for something else. |

| doesn’t matter | 5 | It’s the concern of the town, Citizens of that town should be the ones to decide, It is not in my town |

| undecided | 2 | Matter of the neighbouring town, loss of jobs and new positions, no exact information, everything has its pros and cons, competitions, distance between stores, new jobs, building on the plot, choice of the customer, existing supermarkets, increased traffic, pollution, destruction of small shops |

| Initial audit | ||

| Comments | ||

| agree | 9 | Better choice of goods, more competition, more quality products, lower prices, new work opportunities |

| disagree | 12 | Decrease in work for local farmers, increase in prices, existence of similar stores, threat of outflow of money from the region, job cuts, threat to local small business owners, decrease in available land (other use), I do not agree because we can use already existing structures for the store, more traffic on the roads, disappearance of small shops, bad quality produce, more noise at the location |

| doesn’t matter | 4 | Every person has his own needs, some people would agree with the construction, others would not, a new supermarket can mean greater choice, it’s a concern of the neighbouring town, I don’t care where I shop |