I teach at a Secondary Grammar school of 350 pupils in the Czech Republic. Most pupils come from villages and small towns, rarely coming in contact with people from different backgrounds or experiencing extremes of poverty or luxury.

Selection of activity and class

I selected the activity focused on home to discover what pupils considered the most important thing in their homes and whether they understand that home may be represented by very different conditions. I hoped they would gain increased understanding of different socio-cultural backgrounds, and appreciate that the different environments presented can meet basic human needs: access to water, food, security and safety.

14 first year pupils (age 11 to 12) participated in the activity. I had had no experience of teaching Global Education and measuring attitudes. I assumed that pupils would enjoy this exceptional activity.

First activity audit (Initial audit)

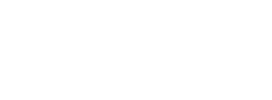

I recounted a story about returning from an excursion, asking students to imagine coming home. I asked them to list what they most looked forward to; these were their parents, a brother, dog, bed, fridge, TV, clean water and keeping warm. They next worked individually on those things they considered to be necessary at home.

Pupil reactions were focused. They tried to answer questions in a way that conveyed how important the feeling of being at home was. All agreed that the most important thing was the people: parents and siblings first, with some mentioning their grandparents. Home was, above all, a place where we love each other, or where people love us.

I presented pupils with a selection of photos of homes. Pupils studied each photo and decided if it represented a home. They were to position themselves on the scale yes; no; I cannot decide.

I asked pupils to justify their decisions and explain which characteristic features of each home were present or absent from each. I noted the answers on the recording sheet, checking that the pupils approved what I’d noted down. All considered the living conditions of the inhabitants of the photos, as well as the reasons they considered such housing a home, thinking carefully about the questions.

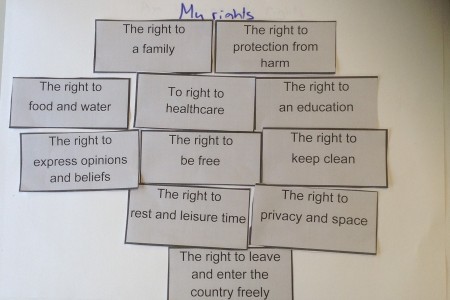

The pupils decided the basic attributes of a home were family relations, security, privacy, freedom (to leave anytime), keeping warm, light, water and cleanliness. Previously they had reflected on what they personally needed at home; now they showed a better understanding of various life situations. Even very poor housing was better than nothing. As for a prison cell, some thought it might offer housing for the homeless over winter. They considered some situations so serious that they were willing to reduce freedom in favour of basic needs such as water, food or warmth.

In the refugee camp, they ignored the fence, focussing on practical issues: it was clean, offered a supply of food and water, and kept families together. Surprisingly two pupils claimed that a released prisoner starting from zero was better placed than inhabitants of the block of flats.

The pupils´ comment: It is the only home they have (of the homeless shelter) seems a reflection on the limited choices of those who have little say in their way of life. They were aware of the social isolation of homeless people – the opposite of their own need for close family relations.

Pupils remarked on a decreased feeling of security with regard to homes atypical of the Czech Republic such as slums. They suggested that the inhabitants could easily lose their homes but simultaneously emphasized that the slum met the social needs of its inhabitants. They perceived the way of life as communal and relations in the community as close. They were also satisfied that there was access to water.

They suggested that For people in Africa it is fine because they are used to it, they can be quite satisfied even if it is dirty. Pupils could thus not imagine this housing for themselves, but assumed it was sufficient for those who were used to it. They did think that inhabitants of slums were disadvantaged compared to people living in an urban zone, who had job prospects and access to food and drinking water.

Mid-phase teaching

This was the first time the pupils had thought about slums or refugee camps. I decided to focus primarily on increasing their awareness of the complex life situations of people in different parts of the world. We discussed what might be important in a home for different countries and social groups, in comparison with pupils’ own original lists. They recognised that they could live without a TV or computer, but that these things represented comforts and a connection to the civilized world. They would not want to lack money, and a bed, table, toilet, running water, pets and garden were very important to them.

Second audit (final audit)

Here pupils chose between 16 different attributes of home: Books, People, Bed, Toys, Money, TV, Water, Food, Garden, Pets, Computer, Light, Warmth, Table, Door, Toilet.

There was no significant shift from their original: Home is where people love me, which stressed human relations: unconditional acceptance by the family, safety and stability.

Two more stressed money, believing it key for ensuring good housing. One chose TV, as a place where the whole family meets. All circled water (compared to 12 in the first round) and food, influenced by those Homes where access to drinking water and sufficient food was not straightforward. Light was circled by nine pupils (compared to seven in the first round) and warmth by all. Toilet was circled by only three (compared to eight in the first round) because pupils focused on things providing security, comfort and essentials, although it was clear that they would not want a house without a toilet.

I presented pupils with a second set of photos of homes that fitted into the same categories as in the first round. I chose:

| 1 |

Luxury single storey house with a terrace, with perfectly mowed lawn and a swimming pool. |

| 2 |

Homeless shed – sheet of plastic attached to poles, cardboard for a door, inside a bed and blankets, small table, snow all around. |

| 3 |

Big firm tent with wide base and doors – in the middle of an urban area, snow all around, but the tent with a base seems to be thermally insulated. |

| 4 |

Wooden shelters for poor on the riverside – sliding doors, distribution pipes, disorder. |

| 5 |

Slum – huge expanse of tin houses, against an urban area background, full of garbage and dirt. |

| 6 |

Refugee camp in Turkey (symbols on the tents) – fenced area, obviously confined conditions in small tents, at first sight a clean environment. |

| 7 |

Prison cell – a bed, heating, wash basin, toilet behind a partition, door bars. |

| 8 |

Block of flats (Petrželka in Bratislava), hundreds of identical windows and balconies. |

| 9 |

Children´s home: from the outside – fenced building with playground and a swimming pool |

Pupils worked independently, instead of in groups, deciding for each photo if they considered it to represent a home and noting down their justifications. Responses varied more than in the first round. All liked the Luxury house best. The Slum’s proximity to a town for some gave its inhabitants a chance to find a job and thus a way out from this unsatisfactory housing. But most insisted that it was not a home because it lacked privacy, security, clean environment, access to water and food. The Block of flats was now more acceptable to pupils: they felt most of those living in the other housing would be grateful for this type of flat, arguing that flats which seemed unattractive from the outside could be well-equipped and that one could live in privacy in a flat. Some also decided that it was a relatively cheap way to live while families saved some money in order to move to better housing.