Background

I teach in a large urban Secondary school and have been embedding Global Citizenship in my teaching for many years. The pupils here are predominantly white-English ethnicity.

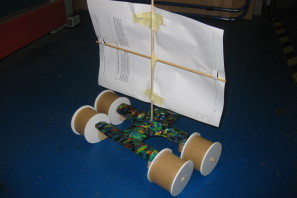

This case study was carried out over 12 weeks with several classes of 11-12 year olds undertaking a Design and Technology project: a prototype of a land yacht leisure vehicle. The vehicle had to be wholly powered using wind energy, thus having a global footprint significantly lower than that of other leisure vehicles e.g. beach buggies or quad bikes.

In addition, pupils were encouraged to make the most sustainable design choices to minimise the damaging impact on the environment and the planet as a whole. This resulted in a considerable amount of time being spent considering actions they could take for a more sustainable future, and experimenting with re-using and re-claiming materials. The balance between function, style and environmental impact is always a difficult challenge for designers.

Measuring activity

Without the emphasis of sustainability on the project we assumed that, given the choice of brand new wheels, masts and sails or glossy (as opposed to slightly flawed) High Impact Polystyrene (HIP), the pupils would have selected the most glamorous and non-sustainable choices. The teachers hoped that, since sustainability had to be kept in mind, pupils would make innovative, more sustainable design choices.

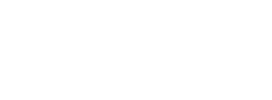

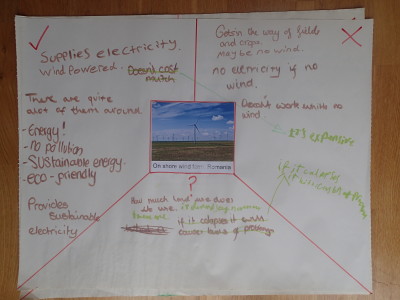

Initially, pupils had the chance to mind-map their first thoughts. They then began the design process. In the early stages, they carried out a group diamond ranking activity. They had to arrange nine statements about dealing with waste that they had previously explored and defined in class (Recycle, Refill, Reuse, Reclaim, Rethink, Refuse (vb), Repair, Recharge, Reduce), putting the actions that they thought had most impact for a sustainable future at the top of the diamond, and those having least at the bottom.

Following the activity, a whole class discussion reinforced the understanding of the concepts. For homework, pupils were presented with nine different circular items (milk bottle tops, coke bottle tops, discarded CDs, tins, cotton reels, construction kit cogs, wooden wheels, Meccano® wheels) that could be used as wheels on a land yacht. Their task was to arrange the wheels in a diamond rank, positioning the most sustainable at the top of the diamond and adding notes so that they could justify their decisions.

The teacher intended to use the Re-Activity statements to measure change in attitudes towards materials and sustainability choices, and then to see the actual design-and-make choices they made when producing their land yachts, and their justifications for these.

The pupils continued going through the stages of the design process – defining a specification list that included points about sustainability – and then designing, experimenting with and making the yacht body, mast arrangement, sails shape, structure and material wheel and axle combinations.

Throughout they were required to consider sustainability alongside style, function and performance – and to justify all of their decisions. The project culminated in a performance test to see how the land yacht travelled when put in front of an electric fan to simulate the wind. The pupils had to evaluate the success of the land yacht with their specification points in mind.

The impact

Initially when the pupils completed their homework of defining the Re-Activity words they showed good understanding of the terms but mostly forgot that the process of recycling itself was energy consuming. Subsequent discussion was animated and passionate, teachers having to curtail it in order to have time to complete the whole activity. Pupils adjusted their definitions and added more to explain the semantic subtleties.

The following week the pupils completed the diamond ranking, discussing what they remembered about the nine words and their implications for sustainable choices. At first, the small group work was varied. Some groups put the attitudinal words like Re-think and Re-fuse towards the top and Re-cycle at the bottom, as they agreed this was the most high-energy consuming. Some placed attitudinal actions towards the bottom, saying that what people think would have little impact for a sustainable future.

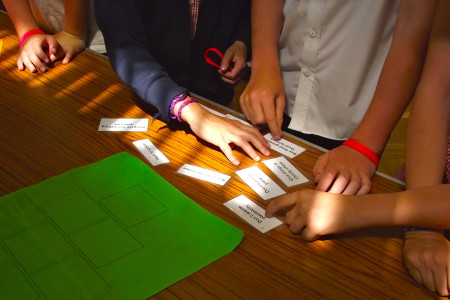

The teachers drew the activities together in a whole class diamond rank activity, initially identifying the least contentious of the nine words, and placing them in fairly unanimously agreed positions. Then groups volunteered the position of the rest of the Re-actions, justifying their decision. If groups strongly disagreed, they also had to justify their decision. Eventually the whole class established a complete diamond rank with Re-cycling towards the bottom and Re-duce towards the top. The teachers felt confident that all pupils understood and could explain the differences between recycling and reusing and that energy consumption was one of the biggest factors for sustainability. The final diamond rank wheel activity, completed individually, included justifications about raw materials, harm to the environment, recyclability, and energy.

Teachers had expected to see strong evidence that pupils used what was learned through the Re-Activity and diamond ranking exercises. Many pupils made frequent reference to sustainability throughout the design process, specifying for example, the use of least 2 reclaimed materials in their land yachts, or a sail made from an unwanted plastic carrier bag. Some were determined to use recycled HIP to make the land yacht body; others wanting to use the new HIP were keen to design a shape that would minimise waste, and ensured all off-cuts were added to the recycling box.

A few were particularly determined to design and make vehicles using predominantly reclaimed or recycled materials, and to minimise waste where new materials were unavoidable. These pupils used the correct terminology, revealing a full understanding of the difference between recycling and reclaiming, an eagerness to spread the word and a will to take positive action by using less energy and fewer resources.

However some pupils made tenuous or no reference to sustainability, only considering the style and performance of the land yachts. When it came to evaluating them, almost all evaluative comments related to performance, rather than sustainable design. For example, they talked about how far and fast their land yachts moved, how smoothly the wheels rotated, how straight the line of movement was, how the sail ‘caught’ the wind, how stylish the land yacht was, etc. No pupil evoked the benefits of people adjusting their hobby interests to those that are less fuel-guzzling, and yet this was included in the initial brief statement.

Pupils completed land yachts; some made using recycled HIP

Reflection

The diamond ranking activity was used both as an audit to gauge the initial understanding and attitudes of pupils, but also for teaching. Thus measuring the impact was not achieved by repeating the activity, but through examination of how pupils made their design, make and evaluation decisions.

In the plenary sessions, pupils successfully explained aspects of sustainable futures, carbon footprints, reducing energy consumption, ecology, pollution and the over-exploitation of the earth’s resources. Although all pupils seemed to grasp the concepts of sustainability and dealing with waste, few took positive sustainability actions themselves when making and testing their land yachts.

When constructing the land yachts, it was more difficult for pupils to use reclaimed materials, such as bottle tops, as adapting these into strong and stable wheels required more thinking, more perseverance, greater imagination and stronger practical ability. Using new and bespoke materials was easier, and some pupils unhesitatingly took this route. Initially most experimented with reclaimed materials; some then selected new, untouched materials whilst others persevered with the more challenging route. The teachers have realised that ideally more time developing pupils’ skills would help them achieve more success in designing and constructing with reclaimed materials.

The teachers have concluded that they were responsible for the lack of sustainability action from the pupils. Since one of the assessment criteria evaluated pupils’ practical capabilities, the focus was on how well the land yacht was designed and constructed, and thus ultimately on its performance (how far it travelled). The teachers hadn’t allowed enough time for testing and evaluating the carbon footprint of each land yacht. They are working on devising an activity in which the pupils will devise their own carbon footprint scale, and measure the success of their land yachts using this too.